Visual communication—photography, videos, films, animation, drawing, illustration, infographics, posters, art and even the images built in our imaginations through the narratives we hold—has the power to evoke emotions, convey realities, craft narratives, act as testimonies and mobilise change. In an age where the human attention span has shrunk to just a few seconds, and screens dominate our lives, visuals are more critical than ever. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words.

For Palestinians, the power of visual storytelling holds profound significance. Israel’s ongoing denial of the right of return, and severe restrictions on access to Palestinian land for both Palestinians and internationals, mean that, for much of the world, the only connection to Palestine is through the lens of those who can capture it.

However, even this act of visual representation comes at a tremendous cost. Israel has long targeted Palestinian journalists, photographers, filmmakers and artists, with the intention of erasing Palestinian realities. Palestinian photojournalist Fatima Hassouna was killed in April 2025, just a day after a documentary featuring her work, Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, was selected for screening at the Cannes Film Festival.

Fatima’s murder is not an isolated attack. Israel’s genocide in Gaza is the deadliest for journalists in modern history, with more killed there than in both World Wars, the wars in Vietnam, Yugoslavia and Afghanistan combined.

Pervasive censorship, distortion, stereotyping, bias and dehumanisation of Palestinians in mainstream media and political discourse adds to this.

Visual communicators therefore bear a critical responsibility: to challenge, rather than reinforce, misrepresentations. This responsibility extends far beyond those capturing images and videos or creating art—it includes those who edit, post, caption, exhibit, distribute and commercialise these visuals. Each step in this process shapes how these visuals are framed and understood, carrying the responsibility to ensure that the context, dignity and agency of those depicted are respected.

This section examines harmful visual representations related to Palestinians and Palestine. While the analysis is centred on Palestine, many of the insights apply to other contexts where colonialism, racism and exploitation persist, and where visuals often reinforce harmful representations.

Like other forms of communication, visuals often reduce Palestinians to dehumanising binaries: they are either depicted as “inherently violent” or as perpetual victims.

On the one hand, visuals tend to overemphasise children, women and the elderly: children running barefoot through dusty refugee camps, women huddled amidst rubble, elderly people leaning on crutches as they are being displaced, crowds desperately chasing after aid trucks. While these scenes capture real moments of hardship, they are often decontextualised thereby stripping Palestinians of their dignity and agency, and reducing them to objects of pity.

On the other hand, Palestinians, especially men, are often depicted as “inherently violent”, with imagery focusing on moments of so-called “escalated” violence: masked youth hurling stones, armed fighters in dark alleys, chaotic crowds. These scenes are framed to convey aggression and danger, reinforcing stereotypes like the “terrorist” or “irrational angry Arab.”

How Hollywood has demonised Palestinians as “terrorists” and violent

Source: Reel Bad Arabs Documentary

This binary denies Palestinians from being seen as full, multifaceted human beings, obscures their reality and undermines their dignity and agency.

*Explore more on stereotyping in this section

In 2019, we conducted a project that explored the visual representation of Palestinians. Participants shared how they perceive themselves, while also describing the ways in which they see themselves being portrayed internationally. The findings illustrate the gap between what is perceived to be communicated versus what is real.

Mays, Communications Manager with Build Palestine:

“The portrayal of Palestinians in mainstream media often rests on a reductive dichotomy: we are either depicted as helpless victims or violent resistors. The full complexity of our lived experience is frequently overlooked. While we undeniably endure the brutal injustice imposed upon us, we are more than the sum of our struggles. We are writers, poets, musicians, scientists, entrepreneurs, creators, innovators. We are a people who continue to envision a future despite the weight of our reality. We seek joy, not as an escape, but as an act of defiance. We savor life not in spite of our circumstances, but because of them.”

Sama, Media and Communications Project Advisor:

“The media shows us as needy people, dirty and poor. These narratives kind of whitewash it by picturing this dirty look with a smile. Also, using big tanks of garbage and a toy. But you barely see in the media that we are trying to make a change. It is a matter of social participation. We have initiatives and social movements that are impactful, for example, using a deserted land, planting in it, and selling organic products. We connect with the land and from the income support other community initiatives. Social participation to me is to teach my girls to be active survivors and clean the trash off the streets instead of passively criticising the culture.”

Mohammad, Filmmaker and photographer

“The official media calls us ‘the children of the stones.’ But all human beings are the same… I mean, you have photographers everywhere and we are not the poorest, most dangerous area in the world. There are places that are much worse off, and they have photographers and artists too, and everyone should know that without having to look at an image. But this image [the image on the right] could be used just to break the idea of Palestinians as just throwing stones or women hugging olive trees. Palestinians with dreadlocks exist as well.”

Orientalist representation across film, art, media, politics and development has long dominated the visual portrayal of people of colour, including Palestinians, reinforcing stereotypes, colonial narratives and dehumanising tropes.

Imagery of Palestinians frequently exoticises them as inherently dangerous, violent, backwards and mysterious; emphasising their perceived “otherness” through a set of simplistic, romanticised or fetishised traits.

Common tropes include depictions of Palestinians as primitive or frozen in time, reinforcing the idea that they are disconnected from progress. This is often reflected in recurring visuals of veiled women, Bedouins on camels, or shepherds wandering through fields.

Other orientalist imagery relies on the familiar binary of the passive victim versus the inherently “violent savage”.

Ultimately, these orientalist visual representations position Palestinians as objects of curiosity, fear or pity rather than as active agents with rich cultures and civilisation, diverse identities, and a noble political struggle. This reinforces a sense of distance between the “civilised” West and the “exotic” non-West.

Trailer of Documentary “Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People”

Depoliticisation and commercialisation of resistance symbols and trauma is now common. Palestinian identity and experiences are reduced to a series of exotic, consumable aesthetics, stripping powerful symbols and images of their political significance and transforming suffering into marketable content.

Examples include:

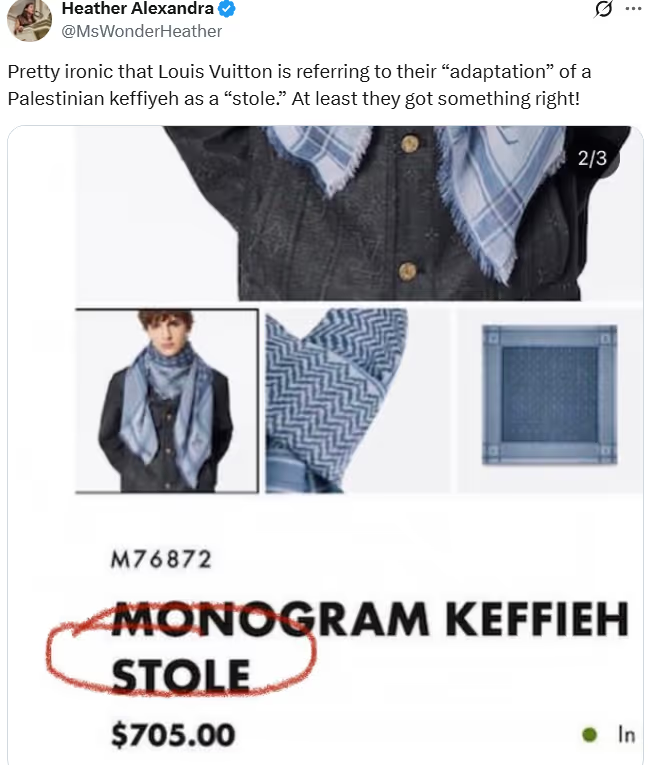

Commodified Resistance: symbols like Handala, the cartoon refugee child by Naji al-Ali symbolising sumoud (steadfastness) and the right of return, are reduced to decorative items like stickers and phone cases. The kuffiyeh is similarly appropriated into luxury fashion, rebranded as a $700 designer scarf.

Commodified Trauma: Images of Palestinian suffering are often exploited by international charities and humanitarian organisations for fundraising, reducing ongoing colonial violence to marketable “crisis” imagery.

Images and the ways in which we reproduce them contribute to imagining realities and accepting snapshots as facts. In Palestine, the paradox is that any representation of oppression also runs the risk of reaffirming its existence rather than opposing it.

Repeated depictions of rubble, checkpoints, or the apartheid wall can transform these tools of oppression into a recognisable “look” associated with Palestine—an “aesthetic” rather than evidence of injustice and an urgent reality to be dismantled.

There is also a tendency to romanticise Palestinians themselves. Visual portrayals often cast them as heroes, icons of sumoud (steadfastness), or mythical figures of resistance—whether in a viral photo of a child throwing a stone or an artist’s rendering of a journalist as a superhero.

While there is no doubt that many Palestinians embody heroism through their bravery in resisting Israeli oppression, the danger lies in flattening Palestinian humanity into symbolic archetypes and risk erasing their vulnerabilities, and their grief. This aesthetic of heroism frames steadfastness as a voluntary choice rather than the imposed condition of colonial violence. By circulating these visuals, representation risks numbing audiences to Palestinian suffering, shifting the gaze toward admiration of strength instead of the urgency to confront the genuine suffering caused by the colonial reality.

*Explore more on stereotyping Palestinians as heroes here

Palestinians are often photographed without consent, and their privacy and preferences are dismissed as secondary. This is the case particularly when photographing children without engaging them or their parents, reducing them to tokens of victimisation or visual symbols of a struggle without their permission.

Similar practices occur when Palestinians are photographed in vulnerable moments—such as being injured in hospital or receiving aid—without regard for their dignity. In protest contexts, photographs taken without care can likewise put individuals at risk, exposing them to surveillance, arrest, or other forms of repression.

The lack of consent and active engagement in these contexts is unethical. It strips Palestinians of their agency and dignity, reinforces dehumanising narratives and can expose them to safety risks.

Social media guide for travellers

Source: Radi-Aid

White saviour complex, sometimes called white saviour syndrome or white saviourism, refers to white people who assume they know what’s best for people in the global majority. They believe—whether as an unconscious or explicit bias—it’s their responsibility to “save” and support people of colour whom they perceive as lacking the resources, willpower and intelligence to do so themselves.

Visually, this often manifests in foreigners taking photographs that centre themselves as the “saviours,” while disregarding the consent and privacy of those photographed. Such practices reinforce harmful power dynamics and undermine the dignity and agency of Palestinians.

.avif)

Photos and videos of Palestinians resisting are often weaponised by the Israeli colonial authorities to repress, imprison, torture, and even assassinate. Because of these risks, Palestinians have learned to cover their faces during protests, as even the act of protest itself has been used by Israeli colonial courts as “evidence” for imprisonment.

The capturing and circulation of such imagery in media or on social media without care for the security of those depicted reflects a disregard for Palestinian safety.

In Palestine, as in many other cultures, certain communities do not like to be filmed or photographed, yet they will most often warmly welcome foreign visitors. Many Palestinians—this is the case in refugee camps or Bedouin communities—often feel the voyeurism of visitors.

Power dynamics often prevent them from expressing their boundaries, while international journalists, diplomats and researchers often tend to prioritise their own interests at the expense of respecting cultural boundaries and norms.

In films, social media posts, reports and news broadcasts, it is common to pair spoken or written content with simultaneous visuals. These parallel visuals, whether on a split-screen, side-by-side in print, or as background footage in interviews, can significantly influence how the main narrative is perceived.

An illustration of this practice is seen in the media’s use of split screens. On one side, viewers see representatives of Israeli disinformation, portrayed as legitimate and unbiased sources, providing distorted context about the occupation. On the other side, Palestinians are depicted as shouting and angry, often veiled in kuffiyehs. Protesting Palestinians are illustrated in “riot”, while Israeli officials are presented as order to the chaos, as guardians of democracy against “terrorism”, rather than perpetrators of colonialism and genocide.

The decontextualised, often strategic way in which images are used, can distort Palestinian narratives and stories, and reinforce harmful stereotypes.

These recommendations are for anyone using visual content to communicate Palestine, including filmmakers, photographers, artists, content creators, media professionals, development organisations, tourists, activists and the general public to ensure that visual storytelling respects Palestinian identities and experiences.

While the recommendations are centred on Palestine, many of the principles and tips apply to other contexts where colonialism, racism and exploitation persist, and where visuals often reinforce harmful representations.

Human Dignity: People are not objects or symbols; they are full human beings.

Agency and Consent: Prioritise autonomy over image-making.

Context and Representation: Tell the full story and avoid stereotypes or decontextualised narratives.

Do No Harm: Safeguard against physical, psychological, cultural and reputational harm.

Reciprocity & Accountability: Approach ethics as relational and evolving.

Acknowledge Power Dynamics: Be mindful of the power dynamics in the act of visual representation and the impact this has on the lives and realities of the people depicted.

Decentre the Artist/Photographer: Use techniques to shift power in the visual process and centre the agency of the person represented.

Contextualise Representation: Tell the full context and story and avoid stereotypes in order to portray people and stories ethically in their broader environment.

Reject Orientalist Stereotypes: Do not portray Palestinians as “primitive, poor, frozen in time, exotic, inherently violent” or other harmful tropes. Acknowledge how visual representations can reinforce racist, patriarchal and colonial perceptions.

Portray Agency: Emphasise Palestinians as active agents. Capture Palestinian resistance, sumoud (steadfastness) and creativity without romanticising people or falling into victim exploitation.

Cultivate Solidarity, Not Pity: Avoid visuals that portray Palestinians as subservient, submissive or in need of saving. Such portrayals bolster pity rather than solidarity. Instead, focus on visuals that capture agency, dignity and collective resistance.

Show the Fullness of Palestinian Life and Experience: Capture the complexity of Palestinian life beyond moments of Israeli oppression, including everyday routines, culture, heritage and community bonds. Reject the tendency to portray Palestinians solely in moments of hardship or as one-dimensional.

Diversify Representation: Capture Palestinians in their full diversity, reflecting all genders, social classes, religions, cultural norms, geographic location, backgrounds and roles. This includes showcasing men, women, children and elders as students, parents, workers, artists, community leaders, freedom fighters and many others who together form the rich social fabric of Palestinian society.

Challenge the Aesthetics of Oppression: Be mindful that constant representations of destruction, ruins, or heroic figures can unintentionally reaffirm colonial power and romanticise both oppressive structures and people. Use visuals that resist turning destruction or steadfastness into symbols, and instead affirm the lived complexity of Palestinian life.

Avoid Commercialisation of Struggle: Avoid commodifying symbols of resistance for profit or Palestinian suffering as a marketing tool.

Set Your Intention: Clearly define why you want to capture a particular image or video. What message, emotion or action do you hope to evoke? Are you genuinely trying to share Palestinian stories and voices, or is the goal to frame yourself as a hero or promote your organisation’s work?

Deconstruct Your Privilege: Recognise the power imbalance inherent in your role as a photographer, filmmaker or documenter.

Understand the Context: Research or ask about the context and stories from the community you are capturing.

Ensure Participatory Approach and Informed Consent:

Avoid Vulnerable Moments: Refrain from capturing Palestinians in vulnerable situations, such as when injured, when chasing a humanitarian aid truck, or when gathering belongings in distress as a home is demolished.

Respect Cultural Boundaries and Local Customs: Ensure consent and avoid intrusive photography that disregards local customs and traditions, or that could expose Palestinians to reputational harm.

Avoid the Saviour Complex: Avoid turning Palestinians' existential struggle into your edgy social media content. Do not position yourself as the hero in Palestinian stories.

Protect Privacy and Safety: When capturing Palestinians resisting, protesting or in any context where they may be at risk of Israeli retaliation, prioritise their safety by using creative angles and silhouettes that protect their identity.

Provide Accurate Contextualisation: Include captions, descriptions, direct quotes and additional resources that capture the full story and provide context on the place, moment and actors involved.

Use Visuals that Support the Message: Ensure that visuals accompanying interviews, films, social media content or reports do not undermine or distract from the message or story.

Edit with Integrity: Avoid manipulating images, footage or sound in ways that could mislead viewers or misrepresent the depicted.

Balance Storytelling with Safety: Avoid publishing images that could put Palestinians at risk of arrest, surveillance or retaliation. Use protective techniques if need be, such as pixelation, blurring, anonymity or cropping.

Consider the Ethics of Virality: Consider how and where your work is shared and how this might affect the safety, agency and privacy of the people represented.

Explore our Decision Tree tool for guidance on making ethical photography choices here